The Case for Mother Earth: 3 Stories From Katipunan’s Theater Scene

The Case for Mother Earth: 3 Stories From Katipunan’s Theater Scene

Feature art by Abigail Manaluz

For as long as they have been neighbors, the University of the Philippines Diliman (UPD) and Ateneo de Manila University (ADMU) have sustained a rivalry that birthed a term with its own Wikipedia article–the Battle of Katipunan. While most commonly invoked during finals games in men’s collegiate basketball, the phrase also resurfaces in discussions surrounding global university rankings. This year, however, the rivalry takes an intermission for three weekends, as Dulaang Unibersidad ng Pilipinas (DUP) and Tanghalang Ateneo unite in the name of theater for their respective season-ender productions.

Three productions from two university theater companies, all under one ticket pass, already sound like a steal–especially in contrast to the soaring ticket prices of commercial musicals to be staged later this year (looking at Dear Evan Hansen, who dared to charge over PHP 6,000 for prime seats at The Theatre at Solaire). With all three shows having successfully completed their first two weekends–and having seen both productions all firsthand–the final theatrical weekend, beginning April 11th, should not be missed by Filipino theatergoers and here are the reasons why.

Tanghalang Ateneo’s ‘Ningning sa Silangan’

Ningning sa Silangan. Courtesy of Tanghalang Ateneo // Photography by Ariana Jurisprudencia

For what it’s worth, Ningning sa Silangan–and the Jo Clifford play it adapts, Light in the Village–doesn’t break new ground when it comes to its core themes. Poverty, landlord paternalism, and societal stagnation have been explored countless times since the birth of feudalism itself. Yet what sets this production apart is its Brechtian approach: tension-breaking parables inserted mid-narrative, characters directly addressing the audience with fourth wall-breaking commentary, and actors slipping into multiple roles, rendering character names utterly useless. The result is a performance that’s self-aware, stripped of illusion, and deeply reflective, which at times, even echoes the spirit of its neighboring collegiate theater production DUP’s Nanay Bangis–so much so that the two feel like parts of an unintentional twinbill just waiting to be programmed back-to-back.

The narrative is carried by five narrators who collectively unravel a story set in a small, pre-electric village marked by barren land and water scarcity. It’s a community shaped by ideological tension: on one side, Inang Kalikasan and the landlord, figures resistant to progress and desperate to preserve a dying status quo; on the other, the progressive side–embodied by the housekeeper and the landlord’s brother–who yearn for innovation and change. And caught in the middle is the landless farmer, exhausted by labor, grasping for transformation in a world that refuses to let him evolve. What power does he truly have, when the land he tills so desperately isn’t even fertile and his own?

Ningning sa Silangan is many things, but above all, it is thoughtful in how it portrays a community unraveling upon itself. Every facet of the village’s dysfunction is approached with nuance. There are scenes difficult to watch, made all the more affecting by characters who just want to live, to breathe, and to survive. The play confronts how greed, obstinance, and revenge can consume from within–unless one chooses to break the cycle and move forward. And the ending? Nothing short of cathartic. It left me in utter silence, a feat not achieved since 3 Upuan last February. Without giving anything away, it’s an ending that evokes the same emotional rush as that scene from Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon–where the discovery of a certain liquid (black gold) brings elation that is sharply undercut by what’s looming ahead. Except here, it plays in reverse.

The ensemble cast in my show—Elio Severa, Maliana Beran, Cholo Ledesma, Chantei Cortez, and Lyle Viray—were stupendous in their ability to shift between characters with such clarity and commitment, even when delivering deliberately awkward or uncomfortable lines. The live music, carried by unconventional instruments, adds texture and energy that seamlessly blend with the world onstage. But the unsung heroes of this production are the dramaturges, Sabrina Basilio and Nathania Kuy, and the translator, Jerry Respeto. Their work ensures that the adaptation doesn’t merely localize the text, but immerses it in a Filipino socio-political context without losing the original playwright’s intent. In essence, Ningning sa Silangan is a glimmer of hope in a world so consumed in darkness.

Lastly, what struck me the most was the irony between the play’s core message and the setting in which it was staged. Themes of poverty, water scarcity, and barren land feel distant–perhaps even alien–to those raised in environments of wealth, privilege, and excess. Having once applied to ADMU, the memory of its steep tuition and miscellaneous fees remains vivid still. It isn’t a stretch to say that such costs contribute to the divide between the elite and the everyday Filipino. This socioeconomic gap is also mirrored in theater performances in the form of language; English, especially when delivered with a British accent, can feel inaccessible–creating an insurmountable barrier during a live play or musical.

This is why most of the theatrical works that personally stood out over the past year were performed in Filipino, a language that reaches across all social backgrounds. It’s worth commending Tanghalang Ateneo’s 46th season for this choice–all five productions, if not mistaken, were staged entirely in Filipino. Ningning sa Silangan becomes an especially fitting season-ender in this context: a mirror held up to those in power, a spark for dinner conversations, and a reminder that theater’s impact should extend far beyond the walls in which it is performed.

Dulaang UP’s ‘Mga Anak ng Unos’ twin bill

Gitna ng Digmaan ng mga Mahiwagang Nilalang Laban sa Sangkatauhan. Courtesy of Dulaang UP // Photography by Marc Stanley Mozo

One of the joys of watching twin bill plays is uncovering the thematic thread that ties them together. In PETA’s recently concluded Control + Shift, the twin bill—Kislap at Fuego and Children of the Algo—explored the transformative power of new ideas, from patriotism to technology, and how these forces shape the societies they emerge from. In Theatre Titas PH’s Dedma twin bill, the characters’ social standings became its unifying theme as it corroded long-standing friendships and relationships. Similarly, from its title alone, DUP’s Mga Anak ng Unos calls for the concerned entities: a climate crisis that affects not only humans, but also the mythological beings said to dwell deep within our forests.

The concept of several Filipino mythological beings convening to decide the fate of humanity may sound absurd, but that’s precisely the premise of Filipino playwright Joshua Lim So’s Sa Gitna ng Digmaan ng mga Mahiwagang Nilalang Laban sa Sangkatauhan. In reality it’s not that far-fetched as global leaders regularly hold climate summits that end in vague promises and little action (see Guy Maddin’s political satire film Rumours).

In the play, the deities’ assembly is triggered by the aftermath of relentless mining and urbanization, reminiscent of the recently concluded stage reading of Nelsito Gomez’s In the Eyes of the People. While Gomez’s piece focused on water contamination, So’s centers on erosion and landslides. The mythical beings, exhausted by human greed and overconsumption, debate on abandoning humankind altogether, yet even they are powerless to save a dying tamaraw alone. The story perfectly mirrors our reality, where climate activists and environmentalists have the knowledge and will to fight for the environment, but those in power—world and corporate leaders—refuse to act.

The play’s climactic ending shows a powerful metaphor for how collective action is the only way forward, as deities, despite their differences, unite to rescue the tamaraw from falling to its death. Although absurd in concept, Sa Gitna ng Digmaan… captures the urgency of today’s climate crisis through a straightforward storyline and distinctive characters. This imaginative vision is brought to life through the collaborative efforts of So and dramaturges Jem Javier, S. Anril Tiatco, Gaby Asanza, and Alejandro Ventura. Their work elevates what is, at its core, a simple story about solidarity, while also spotlighting lesser-known mythological beings across the Philippines, from the mountains of the Cordilleras to the islands of Sulu. Reimagining these deities on stage also wouldn’t have been possible without the combined contributions of set, lighting, and costume designers Mark Daniel Salacat, Barbie Tan-Tiongco, and Carlis Siongco, respectively. The result is an immersive theatrical experience that transports audiences to a realm where gods mostly argue, but ultimately come together for the sake of the world they once helped create and cultivate.

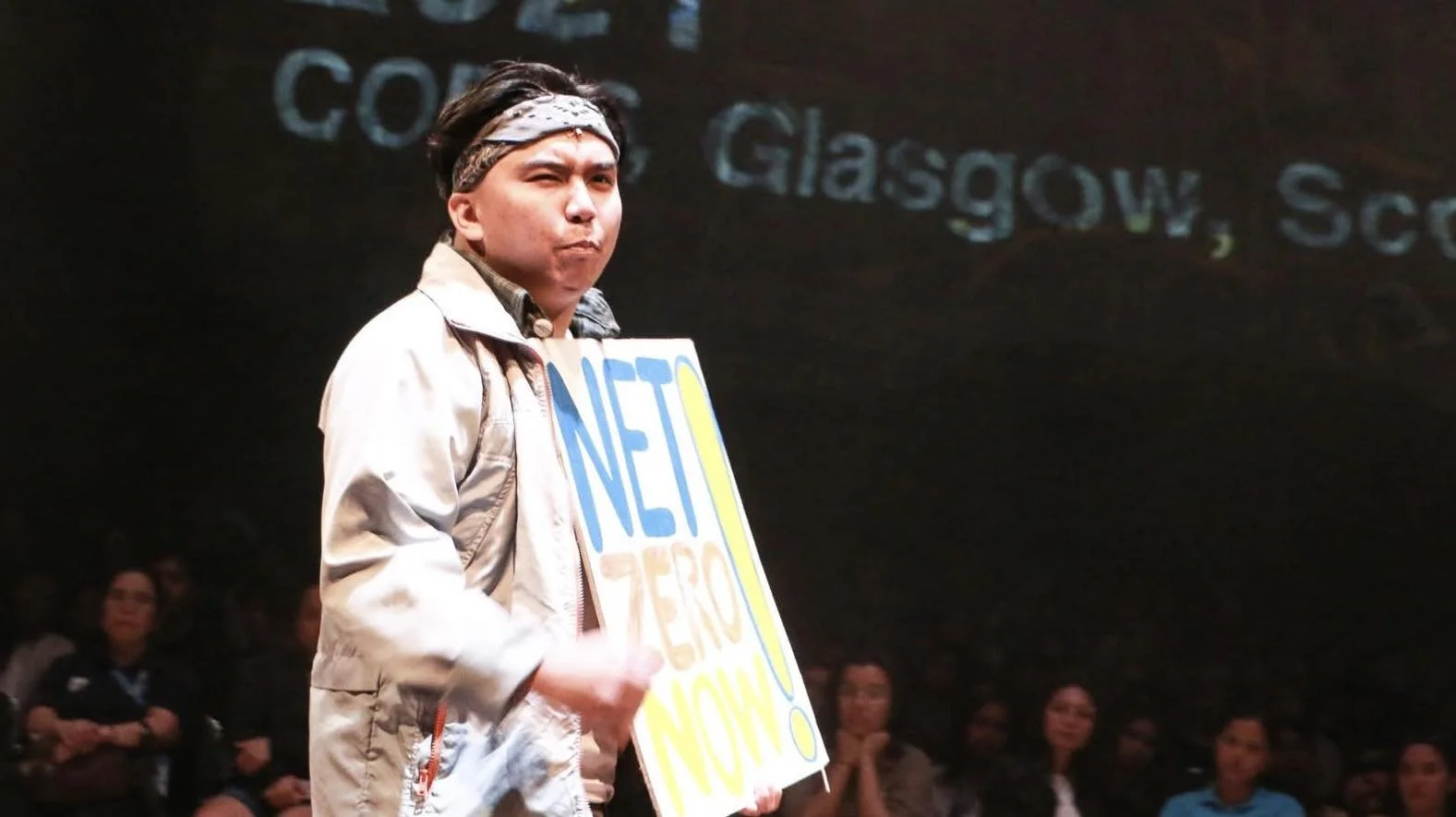

Climate in Crazies. Courtesy of Dulaang UP

While Sa Gitna ng Digmaan… delves into the mythological, its twin play takes a more grounded approach in portraying the current climate crisis. Climate in Crazies navigates through the perspective of average Filipinos trying to make a difference contrasted by news reports, hard facts, and an apathetic therapist that all question the impact of their sacrifices. It captures the frustration of living green and environmentally conscious in a world where individual efforts feel like a drop in the ocean, leaving the uncomfortable question: Is it even worth recycling, composting, being a better person? Fortunately, the play doesn’t just dwell on personal choices, but also focuses on forces beyond an individual’s control, such as corporations quietly pushing back or halting their sustainability targets, and world leaders continuously discussing climate action without setting any firm deadline.

Climate in Crazies can feel overwhelming with the sheer volume of information it lays out—but that’s exactly the point. We act like there’s time left, when in truth, we’re already past the point of no return. Heatwaves will only intensify further, storms will get more violent, and polar ice caps will melt until there is nothing left. The “crazies” in the title barely contains the urgency we should all be feeling based on what’s currently happening. Much like Sa Gitna ng Digmaan…, this production is built on intense research, attributed by dramaturges Nikka De Torres, Neil Shane Alcain, and Chris Joseph Junio, who successfully localized David Finnigan’s work for Filipino viewers. Though the stage design was more withdrawn compared to its twin play, costume designer Carlos Siongco birthed MJ Briones’ attention-stealing garbage bag drag ensemble, effortlessly capturing the morbidity of landfill wastes. Altogether, Climate in Crazies is an unhinged reminder of what’s happening beyond the theater doors and its knocks are something we can no longer afford to ignore.

…So what happens now?

There’s a persistent reminder from all three plays that urge us to reflect, act, and cherish the only planet we have. Whether it be through mythological storytelling, Brechtian performance, or grounded realism, each production confronts the interrelationship of environmental degradation, social inequality, and systemic inaction. Theater should not only be for entertainment, but also inspire us to take action beyond our seats and into the real world. Yes, it can be overwhelming, but what matters is that we keep moving forward—together, deliberately, and hopefully with urgency.

Tickets for Tanghalang Ateneo’s Ningning sa Silangan can be purchased through this form or via Ticket2Me.

Tickets for Dulaang UP’s Mga Anak ng Unos can be purchased through this form, or via Ticket2Me or Ticketmelon.

For Katipunan Theatre Pass tickets, check out this form.